Co-Curator’s Exhibition Catalogue Prologue

Co-Curator’s Exhibition Catalogue Prologue

Diary of an FDS Vinyl Collector

by Arthur Dong

July 17, 1997. New York City. It was awards night for the Asian American International Film Festival and in my hands was a vintage LP of Flower Drum Song’s original 1958 Broadway production. It was a treasured gift from my friend, Kevin Gee, whose mom was the fourth and final wife of Charlie Low, owner of San Francisco’s all-Chinese nightclub, Forbidden City. I had loved musicals since childhood, but it was Kevin who served as my personal guide to the Great White Way whenever I visited the East Coast, camped out in his East Village apartment crammed with theater memorabilia.

I was to be an honoree that night and organizers wanted suggestions for a presenter. That was easy: Pat Suzuki, the original “I Enjoy Being a Girl” gal. It was a hot and balmy Manhattan night, and I was there partly to take home a prize, but mostly to get an autograph from a genuine Asian American musical icon. So, Suzuki gave me the award, which was a nice crystal sort of thing, and before she could escape, I whipped out my LP—yes, on stage. She let out a whopping laugh and signed flamboyantly: “To Arthur, With Lotsa Love. Pat Suzuki.” She must have done that ga-zillions of times, but this one was for me. Kevin, who passed on too early in life before getting his big show biz break, would have loved the theatrics of it all!

So that was the beginning of my FDS (Flower Drum Song) obsession. Well…not quite.

1962 or 1963, or some time around there. San Francisco, Chinatown. The film version of Flower Drum Song was the very first English-language movie I ever saw in a theater. It was booked year after year in one of those neighborhood theaters that usually ran only Chinese-language films from Hong Kong. The theater was always packed with all sorts of Chinese folks—old, young, those in-between, Toishan-speaking, English-speaking, bilingual—and there was a communal excitement in the air. It was a special treat to see Chinese characters, even if they weren’t all played by Chinese, in a real Hollywood movie; it was certainly a refreshing change from the low-budget films from overseas that we sat through week after week. Afterwards, we’d pour out of the theater and there we were:

1962 or 1963, or some time around there. San Francisco, Chinatown. The film version of Flower Drum Song was the very first English-language movie I ever saw in a theater. It was booked year after year in one of those neighborhood theaters that usually ran only Chinese-language films from Hong Kong. The theater was always packed with all sorts of Chinese folks—old, young, those in-between, Toishan-speaking, English-speaking, bilingual—and there was a communal excitement in the air. It was a special treat to see Chinese characters, even if they weren’t all played by Chinese, in a real Hollywood movie; it was certainly a refreshing change from the low-budget films from overseas that we sat through week after week. Afterwards, we’d pour out of the theater and there we were:

Grant Avenue.

Where is that?

San Francisco,

That’s where’s that!

California, U.S.A.!

It was a kind of surreal virtual experience, art imitates life, and vice versa.

January 4, 2004. Fillmore, California. Once in a while, my partner and I would drive to this small town with a population of 13,643, some 40 miles west of Los Angeles, to pick up freshly harvested oranges and to hang out in the town square for a little bit of Americana. The rains were heavy this season. We wandered into a secondhand shop housed in a converted craftsman, and there on the outdoor porch, crusted with mud left over from a recent downpour, sat this Oriental looking piece of furniture. The hand scrawled sign enticed: “Works!” It cried out: “Take me home!” And I did.

Turns out it was a stereo console produced by the Clairtone Electronic Corporation, a long gone Canadian company that once earned an international reputation for combining innovative stereo and cabinetry design in the 1960s. They were probably best known for their then-futuristic “Project G” series that featured globe-shaped speakers and a separate wood cabinet; this was the forerunner for current modular stereos. You can see this set today in museums, in the 1967 movie The Graduate, and if Hugh Hefner kept his, at the Playboy Mansion.

The Clairtone line also included the Mandarin, model #717. The catalogue promises: “Oriental style in smooth ebony finish. Hand carved legs of authentic design” with “brass ornamental hardware accents.” It sold for $449 and all solid-state parts were under warranty until 1973. Thirty years later and it’s still working. Some hums and warbles, but nothing that couldn’t get fixed.

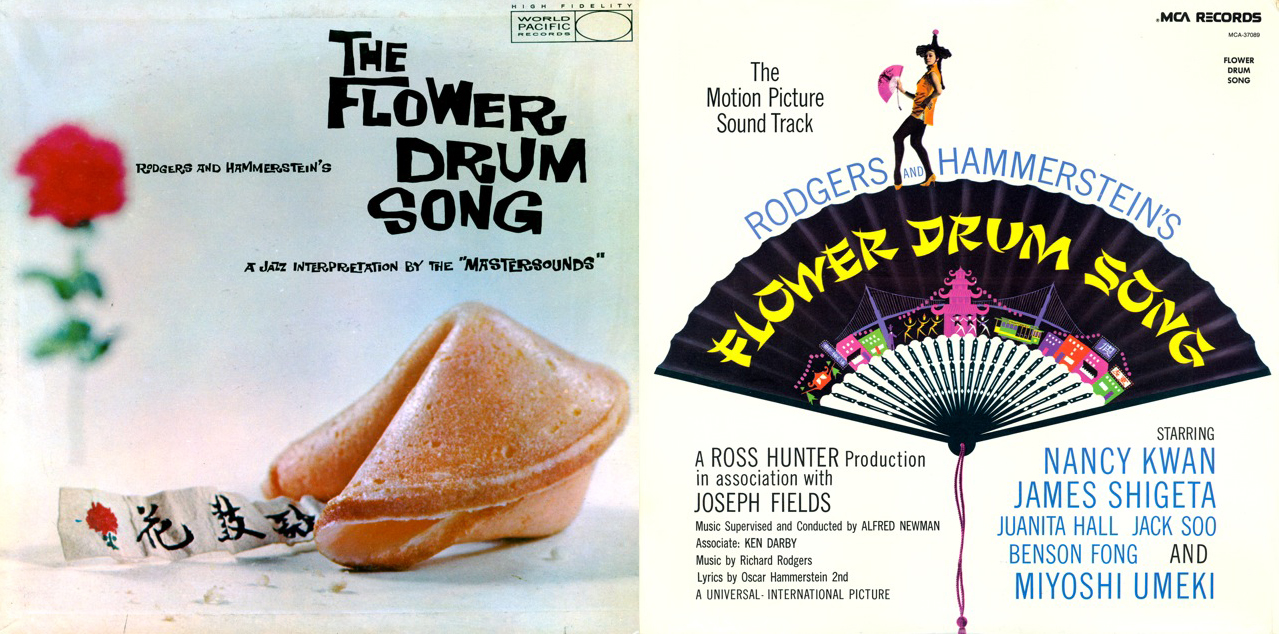

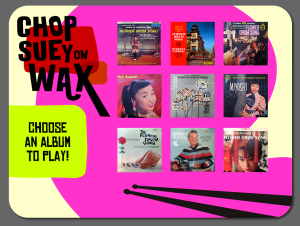

The Mandarin was straight out of Flower Drum Song and would have felt right at home in the living room of the Wangs (the well-to-do family in the musical). A bit of Orientalia co-opted by western technology. Definitely chop suey. All I needed now were albums, but not just any LPs would do…and that’s when my FDS vinyl collection really took off. I was only aware of the Broadway and film versions (and I would never, ever use the one autographed by Pat Suzuki), but one by one, all sorts of adaptations popped up: discount-bin knock-offs, full-blown orchestral performances, sophisticated jazz interpretations, even orange-juice-beauty-queen-turned-crusader, Anita Bryant, cut a 45 of “Love, Look Away” (there must be some irony in that!). As of this writing the count is 42. The breadth was fascinating.

I wasn’t the only one who got hooked.

I have to include my co-curators, Lorraine Dong and Irene Poon, exhibition designer Gordon Chun, and the Chinese Historical Society of America Museum and Learning Center who saw that my collection wasn’t merely a hobby, but a unique aural and visual chronicle of a phenomenon that touched a generation of artists and listeners during a brief period of pop culture history. Of course, a key co-conspirator in this collecting binge goes to my friend, Dan Van Beers, who has spent many an afternoon, hunkered over the innards of my Mandarin Clairtone with his tools and gadgets to restore it to its full glory. And thanks to my favorite graphic designer, Joe Hoffman at Jumphouse Design, who was, as I sneakily suspected, easily tempted to take on the creation of a catalogue that reflected the 1960s. And what a delight to discover that my fellow writers for this catalogue, Ben Fong-Torres and Renee Tajima-Peña, were closet FDS fans all along and joined me on this, my first venture as a museum curator.