The Los Angeles Times

Friday April 18, 1997

By Kenneth Turan

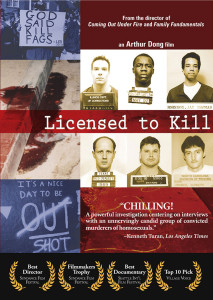

What is most surprising–and most provocative–about Licensed To Kill, Arthur Dong’s strong and disturbing documentary on men who kill homosexuals, is the way it overturns our expectations. Nothing you’ve heard about the plague of violence against gay men will lessen the shock value of this chilling look at the real face of evil.

Winner of the Filmmaker’s Trophy at Sundance, Licensed To Kill is written, directed, produced and edited by Dong (Coming Out Under Fire), a gay man who counts personal experience as the impetus behind this work.

In 1977, Dong explains in a brief voice-over prologue, he was attacked by four gay-bashing teenagers in San Francisco and escaped only by throwing himself on the hood of a passing car. Still attempting years later to understand the roots of this violent behavior, he decided to do “the most difficult thing” and confront men “whose contempt for homosexuals led them to kill people like me.”

“Confront” may not be the right word because one of Licensed To Kill‘s strength is the coolness of its technique, the almost clinical matter-of-factness of its presentation. Dong never appears on camera and wisely allows the half-dozen convicted murderers he interviews to tell their own stories unimpeded by any kind of hectoring or editorializing.

That does not mean that Licensed To Kill is no more than a collection of talking heads. Intercut with Dong’s six prison interviews are various kinds of relevant material, including TV news reports and unsettling police evidence tapes and photos of the murders his interviewees committed.

Equally disturbing are the selections from homophobic statements by prominent fundamentalist leaders, psychotic phone messages of the “Save America/Kill a Fag” variety, a home video of a gay man being viciously beaten up by a neighbor and a police interrogation tape in which a young man calmly describes how he came to stab a gay man 27 times.

But though this material is all relevant and to the point, Licensed To Kill is that rare documentary that would fascinate and horrify even if it were nothing but talking heads. Because while Hollywood’s movies have acclimated us to cliched bigots, cardboard monsters like James Woods in Ghosts of Mississippi or the white racists in Rosewood, it’s a shock to see how various, how unexpectedly well-spoken, how deeply troubled and haphazard the evil that walks our streets can be.

Who would expect to encounter someone like Jay Johnson, an articulate, initially closeted gay man who was raised in a religious, violently anti-homosexual household? Feeling loathing toward all things gay, even “to the extent that I was doing it, I was disgusted with myself,” Johnson was more horrified to discover that his mixed race was a handicap to cruising that made him “unsuccessful at something I already hated.” A series of slayings attempting to frighten gay men off the streets of Minneapolis is what followed.

For some of the prisoners, the murders they committed were almost an afterthought or a whim, the casual byproduct of robberies of gay men who were the classic easy targets. Faced with the choice of a 7-Eleven and its video camera or victims who “because of the fact that they’re a homosexual and they don’t want people to know it, they’re not gonna go report it to the police,” says Donald Aldrich, “who you gonna go rob?”

The most disconnected story belongs to Kenneth Jr. French, a career Army man who killed four people at random in a North Carolina restaurant to protest President Clinton’s relaxing of the ban on gays in the military. And one of the sadder histories is that of William Cross. Raped by a friend of the family when he was 7, he “never felt the same afterward, never felt like I was even a man anymore.” The irrational but deadly result was anti-homosexual rage.

What many of these men have in common, Dong’s film suggests, is the way society’s attitudes in general, and the hostility of fundamentalist religion in particular, gave them an almost literal license to kill, a feeling that slaying gay men meant, as Jeffrey Swinford puts it, “just one less problem the world had to mess with.” “Religion,” muses Jay Johnson, “is a vicious thing.”

To look these people in the face, to hear their horrific but always recognizably human stories, is much more affecting and unsettling than printed summations can indicate. To hear an unrepentant Aldrich coolly comment on the new Texas hate crimes statutes his murder resulted in by saying, “maybe something good will come of this after all,” is to be confronted with the human condition in all its awful complexity.

Licensed To Kill, 1997. Unrated. A DeepFocus Production. Director, producer, screenplay, editor: Arthur Dong. Associate producer: Thomas G. Miller. Cinematographer: Robert Shepard. Music: Miriam Cutler.