From Stonewall to Anita Bryant, to Oregon Measure 9 and “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the Gay Liberation movement has fought for equal rights in a climate of hatred, violence, intolerance, and discrimination. Out Rage ’69, produced, directed, and written by award-winning filmmaker Arthur Dong, is the first installment of The Question of Equality, a four-part film series that shows a multi-faceted history of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement.

From Stonewall to Anita Bryant, to Oregon Measure 9 and “don’t ask, don’t tell,” the Gay Liberation movement has fought for equal rights in a climate of hatred, violence, intolerance, and discrimination. Out Rage ’69, produced, directed, and written by award-winning filmmaker Arthur Dong, is the first installment of The Question of Equality, a four-part film series that shows a multi-faceted history of the gay and lesbian civil rights movement.

The “69” in Out Rage ’69 refers to 1969 — a landmark year for social revolution. While the war in Vietnam escalated, so did the massive efforts of the anti-war movement, with protests raging on campuses across the country. The Black Panthers and the Young Lords took to the streets to fight for the liberation of people of color. It was the year of Woodstock and the Manson murders. While Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, the fight for sexual freedom and women’s liberation swept the nation.

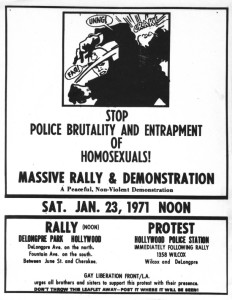

To be homosexual in the 1960s was to risk arrest. It was illegal to operate a business where gay people congregated. Consequently, organized crime controlled gay bars and police raids were frequent. It was during one of these raids, on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York, that the modern radical gay rights movement was born. On the eve of Judy Garland’s funeral in 1969, police stormed the Stonewall Inn and were met, for the first time, with resistance. A riot quickly ensued, spreading throughout Greenwich Village. Through archival footage and eyewitness testimony, Out Rage ’69 tells the story of Stonewall and the heady euphoria that swept throughout the gay community in its wake.

To be homosexual in the 1960s was to risk arrest. It was illegal to operate a business where gay people congregated. Consequently, organized crime controlled gay bars and police raids were frequent. It was during one of these raids, on the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York, that the modern radical gay rights movement was born. On the eve of Judy Garland’s funeral in 1969, police stormed the Stonewall Inn and were met, for the first time, with resistance. A riot quickly ensued, spreading throughout Greenwich Village. Through archival footage and eyewitness testimony, Out Rage ’69 tells the story of Stonewall and the heady euphoria that swept throughout the gay community in its wake.

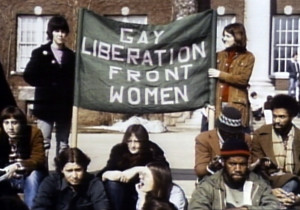

The movement spread like wildfire across the nation, with Gay Liberation Front (GLF) chapters sprouting in cities across the nation, bringing issues of gay and lesbian rights into the national consciousness. But because of the enormous diversity of the gay and lesbian population, rifts began splintering the movement around the issues of gender, class, race, ethnicity, and politics. Put off by GLF’s support of social groups with different agendas (like the Black Panthers), the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) was formed to focus activism exclusively on lesbian and gay issues. Many women, disenchanted by the predominantly male agenda of GAA, formed other groups such as Radicalesbians and Salsa Soul Sisters. As Candice Boyce, an early lesbian activist, recalls, “[The men] weren’t conscious of the oppression of blacks and Latino and Asian people or women. This was no new fight for us.”

The movement spread like wildfire across the nation, with Gay Liberation Front (GLF) chapters sprouting in cities across the nation, bringing issues of gay and lesbian rights into the national consciousness. But because of the enormous diversity of the gay and lesbian population, rifts began splintering the movement around the issues of gender, class, race, ethnicity, and politics. Put off by GLF’s support of social groups with different agendas (like the Black Panthers), the Gay Activist Alliance (GAA) was formed to focus activism exclusively on lesbian and gay issues. Many women, disenchanted by the predominantly male agenda of GAA, formed other groups such as Radicalesbians and Salsa Soul Sisters. As Candice Boyce, an early lesbian activist, recalls, “[The men] weren’t conscious of the oppression of blacks and Latino and Asian people or women. This was no new fight for us.”

Working within the democratic system, the gay rights movement secured limited protective legislation. With the end of the Vietnam war and their growing social power, many gay activists began to relax their efforts and revel in the ’70s, when sexual freedom exploded to the pounding beat of disco.

The tide turned in 1977 when Anita Bryant launched her national anti-gay campaign, “Save Our Children.” Her bid to destroy legislative protection for gay and lesbian citizens struck a chord with many conservative Americans uncomfortable with the country’s rising levels of tolerance. Bryant’s campaign succeeded, marking the beginning of a visible and organized anti-gay movement as similar efforts surfaced across the country. Refusing to crawl back into the closet, activists rose up in even greater numbers, putting aside internal strife.

As Karla Jay says, “We see that we are many different communities, races, classes, all different interests. But the people who hate us see us all as one lump — they see us just as those dykes and fags and that’s why, on some level, we’ll always have to stick together and we’ll always have to fight together.”

Now Available on Blu-ray in two collections: Arthur Dong’s LGBTQ Stories and The Arthur Dong Collection.