Growing up during the 1960s in San Francisco Chinatown, Flower Drum Song was the first English-language film I ever saw in a theater. It was booked in a neighborhood movie house where I usually saw only Chinese imports from Hong Kong. This was a big event: the theater was packed with all sorts of Chinese folks — old, young, those in-between, Toishan-speaking, English-speaking, bilingual — and there was a communal buzz in the air. What a treat to gather together and see Chinese characters, even if they weren’t all played by Chinese, in a widescreen Hollywood musical. Two hours and thirteen minutes later, we’d pour out of the dark theater and there we were:

Grant Avenue! Where is that?

San Francisco, that’s where’s that! California, U.S.A.!

It was a kind of surreal virtual experience, art imitates life, and vice versa.

Then came the Vietnam War, Martin Luther King, Jr., ethnic pride. Flower Drum Song’s kow-towing, pidgin-speaking caricatures were rejected alongside Charlie Chan and Fu Manchu. Songs like “Chop Suey” became an embarrassment for politicized Asian Americans. It didn’t matter that Flower Drum Song was based on a book written by a Chinese American, it was, in the end, a white man’s concoction. Some of my fondest memories in a movie theater became the targets of social and cultural critiques.

Did I miss something? I mean, what Hollywood product, then or even now, gave Asians a chance to take the screen in song and dance, not to mention the swooning looks of James Shigeta and Nancy Kwan. For me, Flower Drum Song exploded with a groundbreaking re-imagination of a people often misrepresented in Hollywood. But there was more to all this than met the eye.

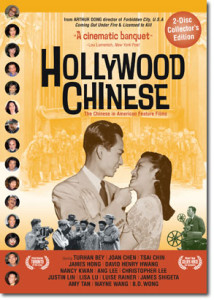

With Hollywood Chinese, I take a lifelong affection for film and combine it with a quest to understand the complexities of cinema. It’s my journey into the world of Hollywood moviemaking, to discover how stories and images of the Chinese fit within an entertainment industry that mixes art with commerce, a universal art form that affects the way we see each other and ourselves. I didn’t set out to produce a definitive encyclopedic treatment of the topic, but rather, a trip through Hollywood as seen through the lens of eleven accomplished Chinese and Chinese American film artists – as well as some non-Asians who played Chinese in yellow-face.

In a way, I’ve been preparing for Hollywood Chinese most of my life. As a kid, I’d venture outside Chinatown and spent hours watching vintage films at local revival houses; I was equally captivated with Jean Harlow, The Apu Trilogy, and of course, Citizen Kane. The experience of looking at images shot decades before I was born was fascinating. I actually had plans to become a film historian, and even though the filmmaking bug hit me, my passion for the archaeology of film has only deepened through the years.

My previous three films have examined the destruction caused by America’s war against homosexuality; I’ve spent ten years covering gays in the military, murderers of gay men, and conservative Christians. Hollywood Chinese was a welcome break from a decade of tense reportage, and a chance to delve back into my love for cinema.

ARTHUR DONG

Follow Us